In Praise of the Field: A Conversation with James Nowak

Facilitated by Kevin Andrew Heslop

Everyone has people in their lives who give them something so precious—and maybe not, at the time, obviously precious, but something that becomes so unquestionably precious—that you kind of just feel obliged to carry it on a little bit. I guess that’s the weight of tradition coming through. And I think that can happen with things that aren’t particularly associated with the word tradition—like, for example, you could learn video editing, something that doesn’t have a long, prestigious, craft guild about it, and you could really feel that what you’ve been given by this other human being or collection of teachers is kind of yours in the sense that it’s yours to take care of temporarily.

Mm.

So I had that at first with woodworking: letterpress came later. I met this man and I think I was fifteen and a couple accidents basically put me in his shop one night. And I remember turning the brass door handle—he had an old nineteenth-century door that he’d fixed up and it had a window on it and it was November and I remember turning the door handle and as soon as I cracked open the door, the light from inside and the smell … it was night time in the winter or late fall and that sawdust—in his case it was White Pine sawdust—and it was warm, bright, pine sawdust mixed with woodsmoke and linseed oil. And something in me was like, This is what heaven clearly smells like.

*chuckles softly*

I was fifteen, just on some kind of erotic cusp—not necessarily in the sexual sense, but that as well—and all of that was just happening: something in a lot of people’s hearts or souls at that moment requires an in-breath of that severity and gravity, and it happened to me there.

Mm.

And he gave me a job at the end of it; I was over the moon, even though I was basically just a barn rat. They were building the new 407 Highway at the time, so he would get contracts to tear down these barns; and initially he was on these demolition crews, but he just couldn’t bear to see these things getting wrecked. So I guess he just kind of stumbled into this compulsion or vocation or whatever you call it to save these old trees ‘cause the way he correctly saw it was these barns were the remnants of the Ontario Old Growth Forests. He could look at a piece of wood and have a pretty good idea of what size the tree was and where and what kind of forest it would have grown in and, Would this have been a tree that would grow way above the canopy or is this something that grows really, really slow like Ironwood? It was apparent to him at a glance just because of learning, no mystical skill—just real, deep learning that was, like all the best learning, undertaken out of love. That turned into a hundred thousand board feet of lumber in his barn and me and a couple other teenagers working. He’d send me out to the barn and say—he had a photographic memory in three dimensions, so he’d say—Go get me that piece of wood, and he would know which one it was, and he would have a bunch of ways to describe it. And you’d go outside and somewhere between the shop and when you get to the barn, you’d have completely forgotten everything he said, so you’d come back and say, Ah, can you tell me again? And I learned all the different species of wood in a couple months without any instruction but genuine confusion. I really grew to love this man, and that love was—and remains—inseparable from my love for what he gave me. He ended up moving away, which was the first real devastation for my little teenage heart—it was no bad blood, but I was unable to work for him—so this kind of possibility that rose up very briefly was suddenly gone.

Mm.

After going to school for woodworking, I was working on these sanders building somebody’s kitchen, and my hands just started to get really sore. It was unexplainable why. And then, you know, they started to get really sore, really sore, and then I could tell that it wasn’t just a repetitive strain injury. Something had happened. It was the start of this infirmity that I now have, which, without any sense of victimhood anymore (although I certainly had at the time), deprived me of my ability to do woodworking. I slowly sold and gave away most of the tools and machines I had. This kind of confluence of ecological, material, historical craft just kind of vaporized in a couple weeks, really.

Mm.

My strength vaporized. I don’t know where it went. And I was honestly just really bored. I couldn’t do anything. And not bored in the sense of a neutral, bucolic boredom—existential crisis boredom.

Mm, mm.

Bored. Profoundly bored. And I was just sufficiently bored that poetry became interesting to me *chuckling*.

*laughs loudly* I love how wonderfully back-handed a compliment to the art of poetry that is: I was so bored that even poetry became interesting.

I think it was Gary Snyder first: there was this guy who just put a bunch of poems of Gary Snyder’s on the internet. It was a really bad HTML website but you could read a few of his poems. And I think Gary Snyder had written some kind of advice to poets and it was something like, Learn your tools and learn your materials. And read a shitload of poetry.

Mm.

Initially my interest was etymology, which is still a big love of mine. I thought, Maybe these are the materials. And in reading these etymologies, I kept seeing all these short forms: OE or AS—Old English or Anglo-Saxon, as you know. I wanted to learn to read those words, and I found this online course for free back when the internet wasn’t an addiction I have—it was something you could go and visit like a library—and it basically taught you how to read and pronounce. So the idea that these sounds were made by people a thousand or fifteen hundred years ago and you could approximate the shape of their ribcage and vocal apparatus and actually put your body in the same shape that they had theirs, for a second, or maybe make some kind of gargled utterance that might be recognizable to them was amazing. Just the intimacy of that was and remains astounding to me. You know, sound moves very close to the heart. It’s right there. And in this way, like pouring the plaster of my words into a hole in Pompeii, you could find a place in yourself like that—I don’t know. It’s just the irreducible distance of that longing that I just found—making those sounds—kind of satisfied me, and still does. With my mind, my imagination, and a good part of my torso, I could face the direction of those people for a little while.

Mm.

But it was out of the question that I could be a calligrapher. It still basically is. It’s painful and I have to steel my dexterity for days ahead if I’m going to do calligraphy. But everybody has something they love so much that they do it to their own detriment. It’s not different. Everybody has that.

It’s interesting and beautiful, this idea of loving something so much that you’ll hurt yourself to do it. And we all have that in different ways, as you say. There’s a lovely Latin phrase here whose pronunciation I won’t get—quod me nutrit me destruit—“what nurtures me also destroys me.”

Wow … Wow, that’s beautiful. It’s definitely nourishing but I don’t know if it destroys me.

Ah, the Latins were a little hyperbolic, but “What nourishes me also discomforts me” doesn’t really have the romance an epigram requires.

*chuckles*

Can we talk a little bit about the infirmity, as you describe it, that led to the boredom?

I mean, anybody who’s spent a lot of time with the doctors has probably done so because they haven’t been able to fix it on their own. And I’ve spent a lot of time with the doctors. I mean, they’re able to diagnose and help a lot of people pretty quickly. If you need a pig valve in your heart, they can do that. So, obviously they have a lot of stuff at their disposal. But I don’t actually have a diagnosis; I just have a description of symptoms that stands for a diagnosis: chronic pain and weakness. That’s why I call it “infirmity.”

Mm.

I like “infirmity.” And everybody suffers, everybody suffers in all kinds of ways. But I don’t want my ability to suffer to be the thing that they remove. My ability to suffer, and to suffer with dignity, is, I feel, kind of under threat when I subject myself to their instruments and all this. Which I’ve done, several times. And I’ve been to the high clinics, the best ones you can go to, and I’m about to start another round to see if we can turn anything up. But the thing that I couldn’t guard against in my younger years—and now I can—is the medical system’s dismissal of suffering as part of the fabric of the world.

Nice.

And amid that suffering, and boredom, and confusion, I found poetry to be helpful—and to be able to say things that doctors just can’t say. And that’s not to say, if anybody’s sick, Go to the poetry section of the bookshelf. Don’t do that. *chuckling* Like, go to the doctor.

*laughs*

But it wouldn’t be bad to go to the bookshelf later.

Nice, nice.

One connection between those the hospital and the bookshelf is Ivan Illich, who wrote about the limitations of the medical system. Initially came to him because he wrote this beautiful book called In the Vineyard of the Text which is about the experience of reading manuscripts in the twelfth century and how that started to change with some innovations in scribal culture—things like chapter headings or marginal notes, early citation systems, and indexes. The example he gives is the alphabetical index: this is obvious to us now as a good way to organize information, but to demonstrate the absurdity of this to students, he’d write the numbers, as they’re spelled, in alphabetical order. You’d start with eight, I guess—E-I-G-H-T. And at the end you’d have three, T-H-R-E-E. He was trying to give us a sense of what this would have seemed like, that the alphabet is to some degree an arbitrary arrangement, resulting in, for example, an entry about monks wearing hair-shirts and a story about a hound being together.

Mm.

So he says that the consequence this has on the mind is that the text becomes increasingly an abstract thing which kind of floats in the ideal or the World of the Forms or something, whereas Marshall McLuhan, broadly speaking, attributes that to the printing press.

I feel like McLuhan is a nice segue into your awareness of Canada as a place in which, occasionally, things apart from grocery lists and treaties and—What does Atwood say? A history written with the blood of bears on the skin of beavers?

So, when I worked for that woodworker, it was a communal undertaking: you needed other people. You need the blacksmith to make the ironwork for the furniture and the hinges; people would come by to buy lumber, sell lumber, buy a machine. He was just a guy in a community. He had a family. But for whatever reason, when I started learning about—I’m not particularly proud of this, but—when I started learning about poetry and writing, I guess I kind of thought of Rilke in his tower or these solitary people distant in time and high above us and inaccessible and just at a great remove.

Mm.

Obviously I didn’t just pull that out of thin air, but all my efforts to kind of explore the tools, the materiality of writing, and also how words are made, were pretty much solitary, partly given the circumstance: I was living on a pretty isolated farm with a lot of work to do and under pretty isolated circumstances. But nothing I’d really done had kind of pierced through this idea that this was a communal activity, despite reading about the communal culture involved in medieval manuscripts, about the herds of sheep and all these pigments and how they were gathered. Nothing really pierced that bubble until I started getting the letterpress stuff. I didn’t know anything—and it’s not like you can just go into Canadian Tire and come out with a letterpress shop.

*chuckles*

I think it was actually meeting Jeremy Luke Hill, really. I knew him from a long time ago but when I moved to this farm I would often think, Man, I wish I didn’t move away from Guelph because I really like Jeremy Luke Hill and I really want to be a part of whatever he’s doing with the Vocamus Writers Community. I just want to be a part of it. He was one of the first people I messaged when I moved back to Guelph. I just sent him a picture of my letterpress studio—which was all in storage at the time—and said, Hey. This is what I was up to. Maybe I’ll get it set up again in Guelph. The mutual interest in this was obvious, so I didn’t have to say much more.

Mm.

Eventually I met you and others through him and he showed me that writing and book production really happen between people. Like, writing literally happens between people. Make all the squiggles you want on a page; you’re just writing your diary. And the only reason you can understand the diary is because other people have spoken to you and written in the first place. So, something about all this kind of broke and I’m a bit embarrassed to say that I held this idea that it was so solitary for so long.

I think it’s an easy assumption to make in a culture in which genius is misconstrued as a noun rather than a verb, but I think of Chomsky here, his sense that language is designed not for comprehension but rather for expression.

Well, I mean, my layman’s take on it would be, If a tree expresses itself, it necessarily does so towards the sun. And its ability to express itself is inseparable from its desire for water. So the idea that language would be different, that it’s just sitting here in the grand void just expressing itself—to whom? And expressing what? The things you have to express if you see a landscape, for example, and feel like you need to express yourself, or you see a woman or a man who moves you, you don’t have something to express without a catalyst.

Beautiful. This is one of the many reasons why I enjoy speaking with you, these bouts of quicksilver you’re capable of.

*laughing*

That was really beautifully expressed, I’ve got to tell you. But tell me more about the evolution of your relationship to letterpress and community.

Well, this is maybe a longer way of coming to the letterpress, but just the idea that when you and I are doodling, or even the worst typography, the worst self-published, terrible thing, those letters originate in carving and then the reed pen; but the way they really get shaped in the western European languages, at least, is through this amazing relationship between a single drop of black liquid and a hollow tube that’s been sharpened and the way that the nib splays when it gets pushed into the page and the limitations of how that can move without making a mess and the real way it can glide and almost sing when it’s really working, that was just astounding to me.

Mm.

And there’s a real through-line between this keyboard—although a lot is lost at various stages—and the cranky monk with his quill and just a single drop of darkness and how it splays onto the skin of an animal.

James.

So my desire to get to do letterpress was maybe a little misguided, but I honestly just wanted to try it. I thought, Well, I’ll just do it. I’ll just make this shop. I’ll renovate this old hunt cabin into a studio. I’ll put a wood-stove in. I was considerably stronger for a brief period, so for a little while I was strong enough to think this wasn’t a crazy idea. And I don’t have any declaration or thing that I’ve seen, ‘cause I’ve done so little of it, but I wanted to experience that change from speech to the hand and the quill pen and the vellum to the paper and the lead. I’d read a lot about it, and I wanted to watch it happen and feel it happen and see if these things that it does to the mind are—I don’t think you can sneak up on your own mind, really, but—to see if they can be married to a muscle memory.

It’s really beautiful, this idea of personally experiencing the arc of human communication through one’s own body.

In terms of the body to do it, it shouldn’t have been mine *laughing*.

*guffaws*

It’s like if I wanted to play lacrosse—

And go from the wooden stick to the aluminum to the kevlar—

It’s like, Dude, get an athlete to try this, you idiot.

*laughter*

That’s great. It’s a moving aspiration.

I find it perennially moving, yeah—and no longer solitary: meeting Jeremy Luke Hill and meeting you, something’s happened since I moved away from that farm I was living on. And my infirmity has also gotten to the point where I did sell one of my presses and I’m thinking about selling the other ones or maybe giving them away. I don’t think I’m going to give them away but the circumstance that I’d really like is—There’s two things.

Attention, reader.

To be able to do this with other people, especially disabled people. It’s unclear whether that’s a good aspiration or not ‘cause a lot of learning needs to be done and I was lucky enough to really learn a lot about woodworking and kind of how machines work and what’s dangerous. I really come to this with a lot of that already. It’s not immediately translatable, but it is helpful.

Mm.

So I’m kind of forced to either give all the stuff up and sell it or see if it’s possible to do it with other people. And then the other thing that’s been really rewarding is just to learn how many great typographers and thinkers about language are in Canada. Some of the books that I mentioned earlier—David Abrams’ The Spell of the Sensuous or Ivan Illich, they’re not Canadian; but we have some incredible thinkers, some of the best: Robert Bringhurst, or this man called Sean Kane, who wrote Wisdom of the Mythtellers, or Andrew Steeves.

Hear, hear.

I’ve really, really loved Jan Zwicky’s writing recently, or Karen Houle. Brilliant thinkers in Canada. I don’t feel like I have a whole lot to contribute typographically. I just don’t. And I think that’s pretty true, but the fact that so many other people are doing this amazing stuff, I’ve found it stabilizing in the sense that I realize I’m standing in the very lower reaches of a mountain range. And I’ve been able to locate myself in the very low regions of that mountain range and very happily so. I felt like a lot of the stuff I was doing previously was characterized by a sense of lostness. I wouldn’t have known it and wasn’t not that bad, but it was just very solitary. And to have begun with an exploration of what are the tools and materials of the language as a very solo thing and to end up basically, in various ways, failing at everything.

*chuckling*

Failing at the calligraphy, failing at the letterpress—just a lot of failure where the thing I thought I could do, the shop I thought I’d set up, the tools I thought I’d bought to use, I was going to be able to establish myself. I felt like what’s actually created a sense of feeling established has been people like yourself or Jeremy Luke Hill or just knowing that these other people are out there. I went to Wesley Bates’s shop last week, the engraver.

Mm.

I met him at a book fair and then I went to his shop unannounced and he had me there for a long time and he was so kind to me and I was so happy to learn a little bit about his work without pretensions to do what he does. And it’s very similar with Gaspereau or Andrew Steeves or Porcupine’s Quill. I don’t know these people personally but I feel like the way some people might feel about farmers if they’re not able to farm: they support their farmers. They feel part of something but they don’t have an aspiration to farm. I kind of feel like that. I do have an aspiration to write and become world famous and have bronze statues all over the world of my likeness, but—

Last time we had this conversation, it wasn’t bronze; there was mention of platinum. I remember diamonds were involved.

*laughing*

There was also, of course, gold inscribed with—I distinctly remember the phrase—“silver filigree.”

I’ve humbled myself, as you can tell, Kevin. Just a few bronze statues and some national capitals.

And some national capitals.

*laughter*

Yeah, we’ll see. But in all seriousness, I’ve really felt the same way about Canadian poetry in the last year as I did when I first discovered poetry for myself. I just got some books from Gaspereau yesterday in the mail; last week I got some chapbooks from Baseline Press. Just to know that these are other human beings who will never have statues made out of them and we’re all just operating and just trying to fucking take the garbage out and cut the lawn, or the equivalent of that. I kind of enjoy that. And then there are obviously a few people who are titans of it. Wesley Bates or Tim Inkster or Andrew Steeves, Gary Dunfield. Robert Bringhurst. He’s amazing. Or Jan Zwicky. Oh my god.

They recently co-wrote something called How to Die.

I haven’t read it but I bet it’s good. Bringhurst is a poetic force like no other.

It is. And speaking of this community, one of the ways in which you’ve participated is through Between Home and Hell: A Chapbook Essay. Just talk me through what that is and how you came to produce it.

That’s an essay I wrote about eight years ago for this publication called Dark Mountain Project. I mentioned David Abram earlier. He wrote The Spell of the Sensuous and is kind of credited with the term the more-than-human community and giving animism a real place in current anthropological discourse. It gets mixed up with whatever the New Age turned into and a few other things but one of the more interesting publications that came out of that circle of ecological writers—by their own description kind of frustrated with writers who weren’t addressing the ecological crisis (this was in 2009 or something)—was this thing they started called Dark Mountain Project. Between Home and Hell initially got published there.

Mm.

It’s about funerary practices in medieval Iceland and what some of the understandings were that inform and generate those practices. What becomes of our dead? Where do they go? What do they mean? Who are they to us? For most of human history, these weren’t open questions that were debatable. You know, “What colour’s the sky?” “Well, go outside and look.” Or, “Are there stars?” “Yes, there are stars.”

*chuckles*

But anyway, the chapbook was an exercise in pragmatism and limitation because I’d originally intended several times to do it on letterpress. I’ve hand-set larger forms, but there was no way in hell I could handset that in my present condition. Then I wanted to hand-set the title page but everything was so infirm. But it was actually great: I did it in InDesign and it’s just a simple chapbook done at a copy shop on nice paper with a nice little hand-sewn binding. But that’s actually really what got me thinking about doing things together, or just trying to get published by somebody else who would make a nice chapbook. Because there’s so many people making way nicer chapbooks than I’ll probably ever be capable of making. The chapbook’s nice; it looks alright; but the reward has mostly been meeting people, giving it away, and just feeling like I could get it out there. And I am happy that it’s previously been published. I think it’s worth passing through certain gates, at least for a beginning writer, before getting your stuff out there. I don’t feel like I answered that question very well.

You’re answering everything beautifully. It’s perfect. This is exactly what I’m here for and you’re doing fantastically. You’re speaking beautiful, measured prose which sounds like poetry.

*chuckling*

It’s suffused with the kinds of aromas that will be invoked when we’re standing along the first of the bronze statues—

*laughing*

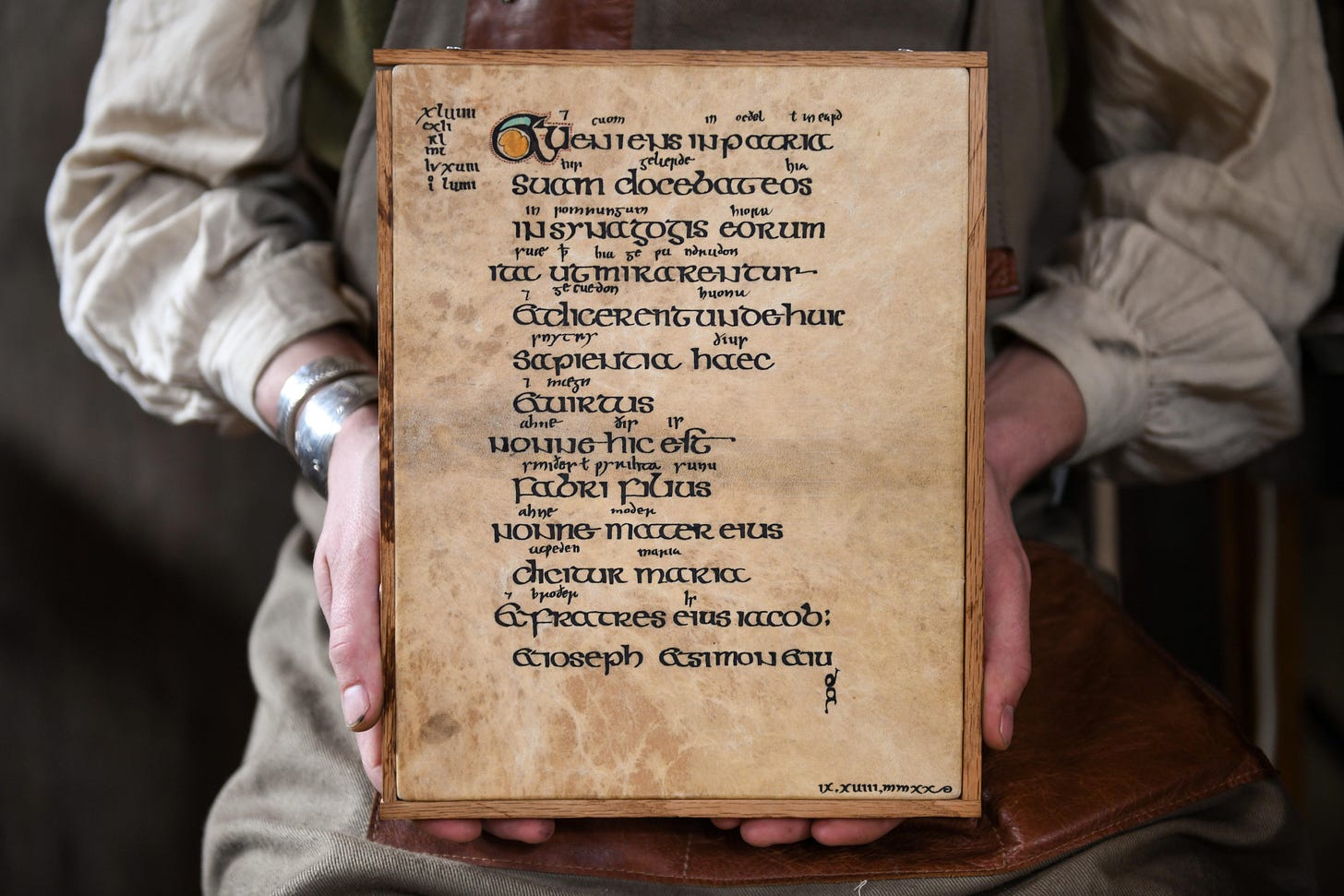

—And the sheet is pulled away and everyone winces as the light refracts off your immortal face for the first—No, everything’s fine. Now, I’m looking at this image of Between Home and Hell and I notice that there are differences between the letters being used. Do you have anything to say in particular about the typography that you chose?

I have very little instruction in this but the book that I do have I used to go to sleep reading. It was Robert Bringhurst’s The Elements of the Typographic Style. I consulted that book ad infinitum. Anyway who knows what they’re talking about would be like, Well you didn’t consult it very well, or you didn’t take to heart the lessons of the book *chuckling*. And I thought, I have to choose a typeface; I don’t even know how to do this. I like those earliest of serif fonts and I think that was set in Adobe Jensen, which is a revival of a very early serif font of the early letterpress printers.

Mm.

Robert Bringhurst pointed out that there was no bold—you couldn’t just click and make it bold—but if a printer of that time wanted bold, the bolds available to him were black letters, which were written with the nib pen or cut black-letter type. So, it’s Adobe Jensen with just a simple—I’m embarrassed to say it to real typographers—a simple black-letter calligraphic font which I think wouldn’t be terribly anachronistic. And because I was writing something from the medieval period, I figured something from the late medieval scribal chancery hand mixed with the early printing press kind of made sense. I think it looks nice. And then the paper is a mohawk vellum 70lb, which I had to go to Spicer’s to get. And then Julia Bussato helped with the InDesign because it was too much for my hands. I kind of said, Like this, and like that. And then she kind of did it, adding her owl skills and ideas. It was both fun and a real exercise in pragmatism because at so many intervals I have to abandon what I wanted to do or what I would have tried to do if I could have my hands on the thing. But I actually enjoyed the pragmatism of it and the process made me in a very, very, very, very small way appreciate the enormous effort that goes into actually making a single chapbook. The furniture making I worked for got to a place where he wouldn’t fret about design decisions: he could move very freely in the material. I imagine some of the people operating the presses now are very much like that—or they’re not always consulting Robert Bringhurst’s reference book. They have actually internalized it and operate according to the principles it lays out. I don’t think I’ll ever get there with the typography, really.

Well, when we’re part of this literary community, everybody contributes something. Even just presence is a really significant contribution. Most people can’t do most things but often you can do a few things and that’s what you bring to the table. Lastly, where are you at with writing? Are you writing? Are you wanting to write right now?

Yeah, learning about chapbook culture is making me desirous to get a chapbook published. I previously thought that a manuscript was out of my league, but a chapbook, one day I just thought, That’s attainable. It’s a difficult, attainable goal. So I’m working on that now, yeah. I started a bunch of erasure poems of this Jesuit text written in the 1670s. I don’t know if these are just going to be stepping-off points to something else or just a fun exercise that’s practice, but the text was written in the 1670s in Lower Canada but a Belgian Jesuit. He wrote it in Huron or Wendat; it’s a religious treaty in Wendat that was then translated into Modern English. These guys are masters of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas and the subtleties of Christian theology; and it’s taking this very noun-based, incorporeal Christian theology and then putting it through a language which is verb-based and basically doesn’t care much for incorporeality *chuckling*. For example, in Wendat the word for bone and soul are the same word.

Mm.

And so you get these almost Sesame-Street sounding explanations because of the layers of translation. You get a Jesuit who wasn’t very good in Wendat translated into English. Like, “There was nothing for him to make things with. He just spoke and something happened.”

James Nowak’s chapbook of erasure poems with Gordon Hill Press, Draw Me the Sky, is available here.

The poems are drawn from De Religione, a work of theology written in the Wendat language around 1670 by Father Phillipe, a Jesuit missionary to the Wendat people in Québec.

The title, Draw Me the Sky, is an erasure of a short phrase in the text. ‘Draw me to the sky’ was the Jesuit attempt to render something close to ‘Help me get to Heaven’ in the Wendat language. As an erasure, the idea of ‘drawing the sky’ imagines various ways of gesturing towards, or approaching, the divine—myth, or even prayer. Soliciting another person to ‘draw me the sky’—to tell me their myths, or to show me how they pray—is a beautiful and intimate request, one that was tragically lacking from De Religione, and from the colonial missionary project in general.

And to read an interview with James on the occasion of his winning the 2024 Canadian Society for the Study of Religion Undergraduate Essay Prize, have a look here.

About Kevin Andrew Heslop

Kevin Andrew Heslop (b. ’92, Canada) made poetry, curatorial, directorial, and screenwriting debuts in the early 2020s and left home for successive residencies in Serbia, Finland, France, Brazil, Denmark, and Japan, dialoguing with artists along the way (forthcoming with Guernica Editions in two volumes of Craft, Consciousness: Dialogues about the Arts).

In 2025, Heslop will share a new art exhibition with Leslie Putnam, of and, from Centre [3]; a new book, The Writing on the Wind’s Wall: Dialogues about Medical Assistance in Dying from The Porcupine’s Quill; and new work via The Fiddlehead, Parrot Art, The Seaboard Review, Astoria Pictures, The Miramichi Reader, and The American Haiku Society.

He is currently writing his feature film debut from São Paulo, Brazil.