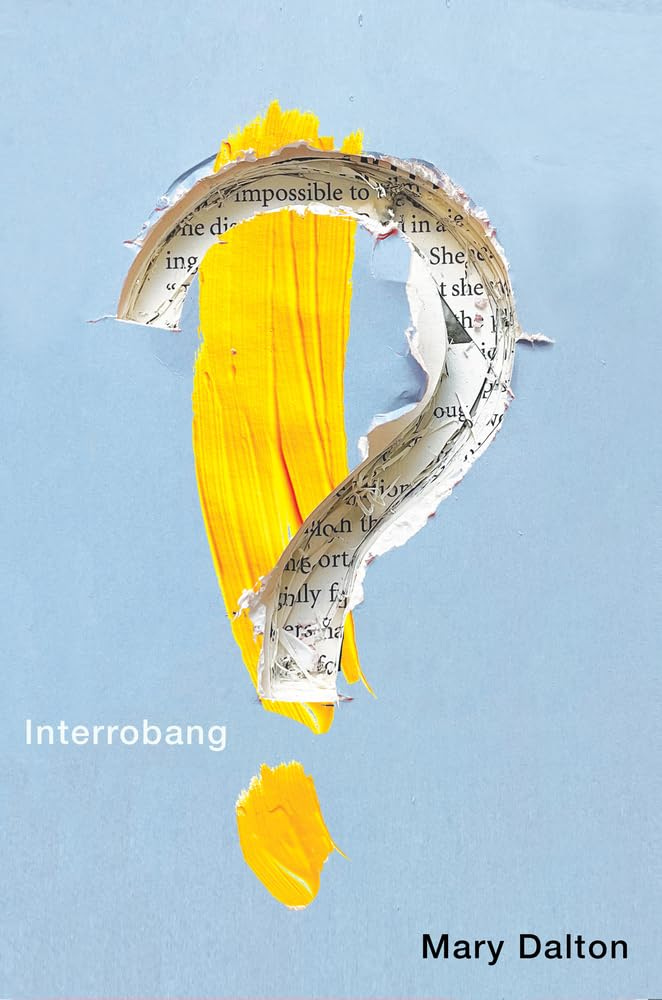

Half question mark, half exclamation, hybrid interrobang is a portmanteau of punctuation. (Its double effect would be even more pronounced in Spanish where these marks precede and follow questions and exclamations like pairs of dangling earrings.) In Mary Dalton’s poetic grammar, interrobang is a “prince” of punctuation, merrybegot in the coupling of question and exclaimed mating, as point penetrates curvaceous question across Newfoundland. Her witty footprints of ambivalence sprint through each section of this collection from “Taking Stock” to the final series of “Alba Poems,” with “All the Clubs from Holyrood to Brigus,” “Waste Ground: Riddling,” and “Triads” along the way.

Two solid epigraphs ground Interrobang. The first is from Clarice Lispector’s enigmatic novel, The Passion According to G.H.: “’I’ is merely one of the world’s instantaneous spasms.” Her instantaneous ego may be rendered through the spasmodic bang of an exclamation mark. The second epigraph, from Emily Dickinson, offers a stanza of questions, exclamations, and signature dashes that function as horizontal interrobangs of identity:

“I’m Nobody! Who are you? Are you – Nobody – too? Then there’s a pair of us! Don’t tell! they’d advertise – you know!”

Again, the ego’s spasm in place of any egotistical sublime gathers the pair of women writers into Dalton’s Newfoundland shop for taking stock of self, common objects, and society. Dickinson’s dance of personal pronouns and exuberant punctuation enters Dalton’s coastal choreography.

The book’s first section, “Taking Stock,” features Maurice Blanchot’s “Everyday Speech”: “The everyday. What is most difficult to discover.” Dalton’s wit and musicality discover the vernacular that joins with her semi-formal epigraphs. “Again. / The lollop of the cow-bell, and / she’s entering that ritual space.” Here, “I” dissolves into the third-person pronoun entering the shop. Even before the ring of the bell, “Again” chimes the sound of ritual repetition. Lines and stanzas lollop, cow-belling stock of a biscuit-box house – the architecture reflecting store’s contents: “two rooms, at once contained, / crammed and cramped, categorized -- .” The catalogue goes on in the bounce of bell and box – their hyphenated rings leading up to the longer Dickinsonian dash at line’s end. Caesuras gather up parts before turning to people: “the youngsters, like the old ones, / the shambler, the steady customer, / the come-by-chance” – this final hyphenation linking people and place in Newfoundland where shamblers and lollopers wend their way in the shop’s internal rhymes.

Long o’s in the next stanza contribute to the reaching out that partners with internalizing crammed and cramped:

“A node of neighbourhood. A cornucopia, spilling over. Old Mother Hubbard’s life-saver. An emporium of sugary bliss.”

Dalton’s vernacular emporium journeys across island and Rock, balancing and’s in the next stanza in place of comma, yet always with the ring and rhythm of enthusiasm and stock characters. The shop’s doors open to the “clutchers of warm nickels, to / young bucks and the grizzled, / bogeyman and gargoyle.” Across the balancing and’s, nickels expand to bucks in a cash nexus, alliterations straddle bucks and bogeyman, grizzled and gargoyle to lollop through the lines. In her clearing house of language, termagant and twiddlers, harridan and hero thrive. Dalton’s clearing house opens to the near and ear of Carbonear and conduit of goods.

Like an Adam or Eve on the island in “The Naming,” she gets the names right, before returning pendulum-like to “The Shop Bell,” which sounds ritual space: “A warm mellow tone – lucky the cow that sported it, / ambling in meadows. The merging of warm into mellow and meadow intones the right note, which is picked up in the long o’s of meadows – a ranging assonance. The cow may reappear in further forms of “chewing the fat” or “hunk of cheddar chopped / from the block.” As a customer leaves, the bell sounds its goodbye blessing in Dalton’s tone of wit and warmth.

The final stanza sets the sound: “Tucked in a drawer, / the bell’s flared mouth now mute -- / yet it / speaks volumes, resounds.” Dalton’s and Lispector’s “I” disappears in the object’s muted mouth, but speaks volumes in shop talk, riddles, and waste ground. Indeed, American poet Ange Mlinko’s epigraph for Dalton’s third section, “Waste Ground,” teases the ego: “… there is much more to life than meets the I.” The “I” meets the outer world and listens attentively to the sounds of Newfoundland with its fanfare of dailiness. Dalton’s wit is intrinsic yet out there in the shop’s money box and blue bottle of cod liver oil.

Her second section, “All the Clubs from Holyrood to Brigus,” begins with an epigraph from John Berger’s study of photography: “Shadows [offer] shelter as can four walls and a roof.” Dalton’s chiaroscuro shades shop and club, Rock and coast, light-housing a vast province. She drops names and scraps of stories in a liquid lexicon of intoxicating grog shop and shebeen. “Girl at the Bar” presents one of Berger’s brief photos, beginning with an epigraph from Frederick Seidel’s “Fog”: “I spend most of my life not dying. That’s what living is for.” Dalton paints her portrait, the I and eye disappearing in the third person: “She is looking into the distance” (following the gaze of Caspar David Friedrich’s “Woman at a Window” and Edouard Manet’s “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère”). The distance and fog of Newfoundland compress into a close-up: “The light touches her forehead, her neck; / hovers about her eyes and chin, / gold strands of her hair, gold of the beer glass.” Realms of gold are contained in the “busy iconography of the bar.” Photography and iconography capture framed memories, blurry clutter and stillness, “a space at once inner / and knowing, a pool of solitude / in the whirl of carnival.” The still point of the knowing stanza contends with the whirl of carnival, an interior pull against outside forces in Dalton’s dynamic verse of stored stories.

The second stanza further develops this portrait of a girl. A list of alliterations accompanies art history: “Here, in the commotion, the crowd, / the photographer’s found / a Botticelli angel, / a Vermeer beauty.” But Dalton redresses her in T-shirt. The photographer’s gaze travels further, like the girl’s looking into the distance: “one senses that soon / the moment will vanish.” In this vanishing point she will slide off the bar stool, toss off a wisecrack, grin at the comeback, and “sashay out with buddy, / out into the lava shift of the strobes, / out into the roiling / spree of the dance floor.” Dalton’s choreography replaces Botticelli and Vermeer with T-shirt and sashay of out and into – Seidel’s fog sliding into Newfoundland, watering holes swallowing Atlantic currents.

In the next section she cultivates “Waste Ground” where parsley is a “prince of temperance” to go along with interrobang’s prince of ambivalence. Her stinging nettle summons Jane Austen who returns in “The Alba Poems” in the last section of the book. Alba appears as a Question Mark (half of interrobang) before morphing into a “Jane Austen manoeuvre.” Alba travels “with questions, wry hope; / with a sharp pen, a history book” that Dalton packs. The list of qualities concludes “with counterpoints and suggestions; / with commitment and queries.”

All over the place, Alba steps and lands with her best protest shoes, interrobang, and Joycean delight in language. Dalton’s short forms charm her larger-than-life land and lore.

“Waste Ground: Riddling” begins with an epigraph from Don McKay’s “Baler Twine”: “The coat hanger asks a question” designed to be answered in Interrobang, particularly in Alba’s “Punctuation Marks” – marks that often serve as masks of identity. The first stanza opens and closes, poking fun at itself: “Time’s pricking. / Dead ends, escape hatches.” “I” escapes to Alba in the second stanza:

“If Alba were one, she’d be an ellipsis – or maybe a dash. A wandering current or a waterfall.”

In Dickinsonian fashion, Alba’s currents quiz the marks in cozy riddles and vastness of commas. She brackets philosophers and politicians: “(The connections are dubious.)” And ends up in another escape hatch: “She’s setting up to / slip inside and away, via / the first likely parenthesis / that happens along.” Interrobang happens along the coast, each wave questioning and exclaiming the alphabet’s instantaneous spasms.

In stores, bars, and stories, Dalton’s chamber music lores language across Newfoundland. Her clipped wit within a cosmic Rock shrouded in fog arouses the hook and cloak of Alba’s interrobang, which may also take the form of “the arc of hand as it pulled / thread through a needle.” Traces of Susan Glickman’s wit and Meira Cook’s jaunty prairie may be found in Dalton’s briny verse, preserved in salt and played in a major key of memory. The sounds and scents of birds and flowers – twillick and tansy – waft through her whimsical, plentiful garden of earthy delights.

About the Author

Mary Dalton’s volumes of poetry include Merrybegot, Red Ledger, and Hooking, as well as two prose works: the miscellany Edge and The Vernacular Strain in Newfoundland Poetry, a print version of her 2022 Pratt Lecture. Dalton’s work has been widely anthologized in Canada and abroad. She has won numerous awards, including the E.J. Pratt Poetry Award, and been shortlisted for various others, among them the Pat Lowther Award, the Atlantic Poetry Award, and the Cogswell Award for Excellence in Poetry. She lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Signal Editions (Sept. 12 2024)

Language : English

Paperback : 80 pages

ISBN-10 : 1550656686

ISBN-13 : 978-1550656688