Mashel Teitelbaum: Terror and Beauty

A Review by Michael Greenstein

Another monumental tome from Goose Lane Editions, Mashel Teitelbaum: Terror and Beauty gathers many essays that pay tribute to the artist’s life and painting. Born in Saskatoon a century ago, Teitelbaum carried the flat aching heart of “prairieness” with him throughout his unsettled and unsettling career. Mood swings, varied influences, and many locales appear in the beautiful and terror-filled reproductions throughout this book.

In “Ways In” Ottawa poet Margaret Cook offers one kind of introduction to Teitelbaum’s Gold and Green (1964). The first section of her essay parses the title: “The painting with the big sun and the big caterpillar. Or, the fried egg.” Domestic and cosmic, the sun is a fried egg that nourishes the greenery and universe. The title fails to mention the other dominant pigment, black, which joins gold to green. Two horizontal lines link the egg-sun to a swirling figure at the right. To the left of the sun a series of black swirls lead downward to black, rock-like shapes, which in turn lead to the head and lower parts of the caterpillar. Black strokes also ladder the upper-right section of the canvas, further activating the gold and green sections. The circle brightens the world, while black lines write and allegorize it.

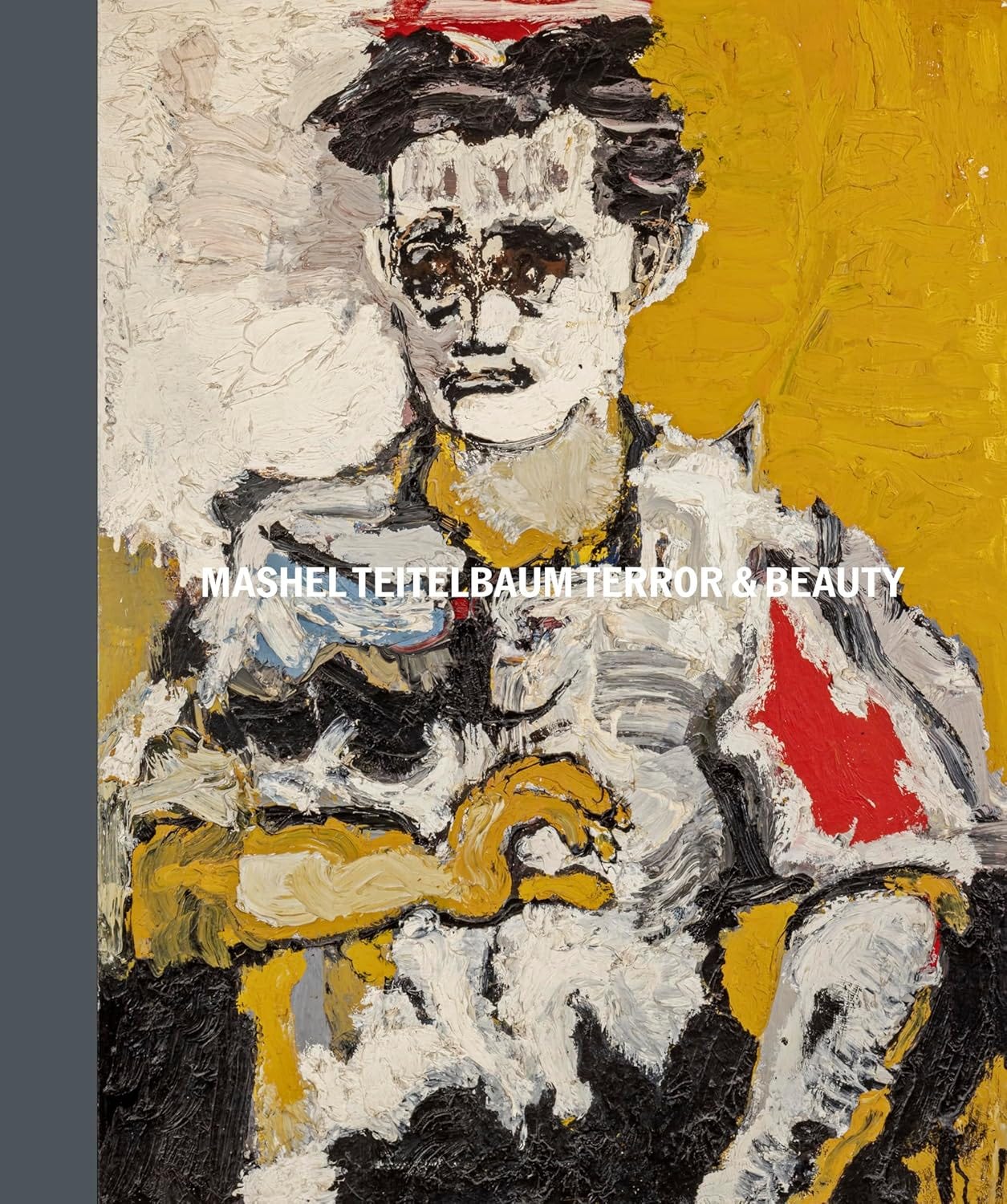

Andrew Kear’s “Circle and Void” examines these shapes in Teitelbaum’s art. Circles of eyes in his portraits are also sources of light, yet deeply blackened in Dark Self (1958), God’s Angry Men (1971), and all of the Self Portraits from the 1970s. The circular finger formation of Dark Self on the book’s cover hints at the emptiness of a brush not clutched. The right horizontal arm reaches to the left bicep entirely in red, as if the artist is wearing his heart on his sleeve of terror. The tragicomic clown wears a hat, another circular feature in many of the portraits where a cowboy hat may represent a displaced head covering from his Jewish history. There is more to these circles than meets the eye, for terror lurks in the eye of the beholder. Yet Teitelbaum is not without humour, as evidenced in Two Gun Teitelbaum, Terror from Saskatchewan (1982). The circular cowboy hat drips black, as do the eyes, while a bloodied vest drapes the torso like a prayer shawl. In Kear’s terms, we witness “orbs of internal opposition”: for the tragicomic cowboy one eye scans a vast horizon, while the other turns inward in time after the trauma of World War 2.

If Margaret Cook confronts Gold and Green as a way in, then Bernice Eisenstein studies Standing Figure with Blue Horizon (1972) in medias res: “… ellipses, a midway starting point of pause and hesitation.” Where Gold and Green is all motion, this later figure in a ground is more static, shaped by acrylic skins of paint. A red circle is surrounded by a blue circle, the roll of wheatsheaf on beige prairie or battlefield. One blue and one black horizontal line suggest a path cut through the beige emptiness, while the standing figure in red and black has the face of a pharaoh, and its arms and chest have an almost wooden grain to them. In Eisenstein’s words, “A landscape has been laid down, and as if released from a two-dimensional plane and pushing itself right up to the edge, stands a figure – red-black laminae, shaped, flattened, wrinkled, pasted – with arms akimbo, staring out through button-hole eyes with an introductory gaze of innocent surprise.” Eisenstein’s “Sightlines” is echoed in a number of other essays that share views and viewpoints with Teitelbaum’s works, their colours shaped and shared.

Sasha Chapman explores the chaos in Litter (1956-57). Of this carnivalesque canvas she writes: “Figures tumble down and across the canvas, moving right to left like Hebrew letters through a roiling red sea of brush strokes.” Dangling keys to the left of centre regard flying forms and figures to the right, one in the shape of a ladder with human feet. She describes Litter as existing between two states – bipolar states of mind in beauty and terror. These two states are also the lyric and narrative strokes, abstract and figurative, image and language, oscillating between the sublime and mundane.

The circle in most instances may be sublime as in Gold and Green or mundane as in Still Life (1957), which portrays an open toilet, its fried egg inside the bowl in embryonic form. In a more somber form two circular wheels appear in God’s Acre (1945), while a smaller circle at the top of the painting represents the sun whose rays reach through the clouds. Alissa Schapiro analyzes this painting in her essay, “The Mills of the Gods: The Impact of Judaism and War on Mashel Teitelbaum’s Art.” The two wheels lean against each other, while a third circle in black emanates from them. These wheels are partly encircled by wheat sheaves that stretch upward towards the columnar rays of light from the sky. Like the desolate prairie wheat, the spokes of the wheels turn to the sky’s rays in dynamic stasis; and this biblical scene in Saskatchewan evokes Ezekiel’s wheels, as the painter-prophet rails against the art establishment. In other words, Teitelbaum’s wheels convey, not passengers, but messages – his Jewish heritage of Bible and Holocaust immediately preceding this painting in 1945.

Earlier paintings already reveal Teitelbaum’s Jewish sensibility. His 1934 drawing, The Wanderer, depicts a bearded and burdened Jewish figure in a biblical landscape with a temple and palm trees (the meaning of Teitelbaum) at the end of the path. With its abject figure headed toward hope, this drawing is bipolar in its layering of biblical scenes over a Canadian landscape. More ominous is his 1939 painting, Miasma of the Mind, which depicts a man clutching a newspaper with the headline “SCARE.” A figure of a death mask in turn clutches the man’s shoulder with elongated fingers. This macabre spectre wears a gas mask that recalls World War 1 even as it prepares for World War 2. Miasma of the Mind and God’s Acre bookend World War 2. Schapiro concludes her essay with the hauntology of the Holocaust: “Whether or not Teitelbaum ever experienced the divine retribution he sought, the artist’s postwar existential angst – manifesting itself in depression, isolation, and feelings of abandonment – continued to haunt Teitelbaum for the rest of his life.”

Janet Warner has drawn a series based on Teitelbaum’s Dead Tree (1958), which features a distorted circle at its core. Werner sees the tree as sculptural, but it is also scriptural as a tree of life filled with gesturing figures. Mangled limbs reach outward, like some kind of crawling beast, while the malformed circle is beige and embryonic in contrast to the dark brown bark -- gnarled burl, bole, and hole. The tree also alludes to Teitelbaum’s surname (date palm tree), while his given name, Mashel, means both leader and allegory. The artist lives up to his name in his allegorical approach in so many of his works.

Like Litter, Sarabande (1963) is a swirl of motions, while Pillar of Fire (1964) is both static and kinetic with its vertical black strokes against an amber background. A later painting, Self Portrait of the Artist as a Split Personality (1971), covers so much of his irony and psyche, the black eyes staring in owl-like fashion, circles in acrylic skin. The black scribbles in Gold and Green and Sunscape come full circle as a means of writing life and allegory. Prophetic wheels sarabande and circle the prairies and an abandoned chariot.

The last picture in this book, “In a Coffee Shop (Self Portrait)” (1983), is a fitting conclusion to this coffee table edition. The black lines of pen on paper write and rewrite his entire life, filling the void from Saskatoon to Toronto’s Kensington Market in this tribute to an artist who deserves this attention.

About the Author

Andrew Kear is head of programs at Museum London. He was formerly chief curator and curator of Canadian Art at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Kear has written and curated exhibitions on a wide range of contemporary and historical Canadian artists, including Karel Funk, L.L. FitzGerald, and William Kurelek.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Goose Lane Editions (Sept. 24 2024)

Language : English

Hardcover : 190 pages

ISBN-10 : 1773104306

ISBN-13 : 978-1773104300