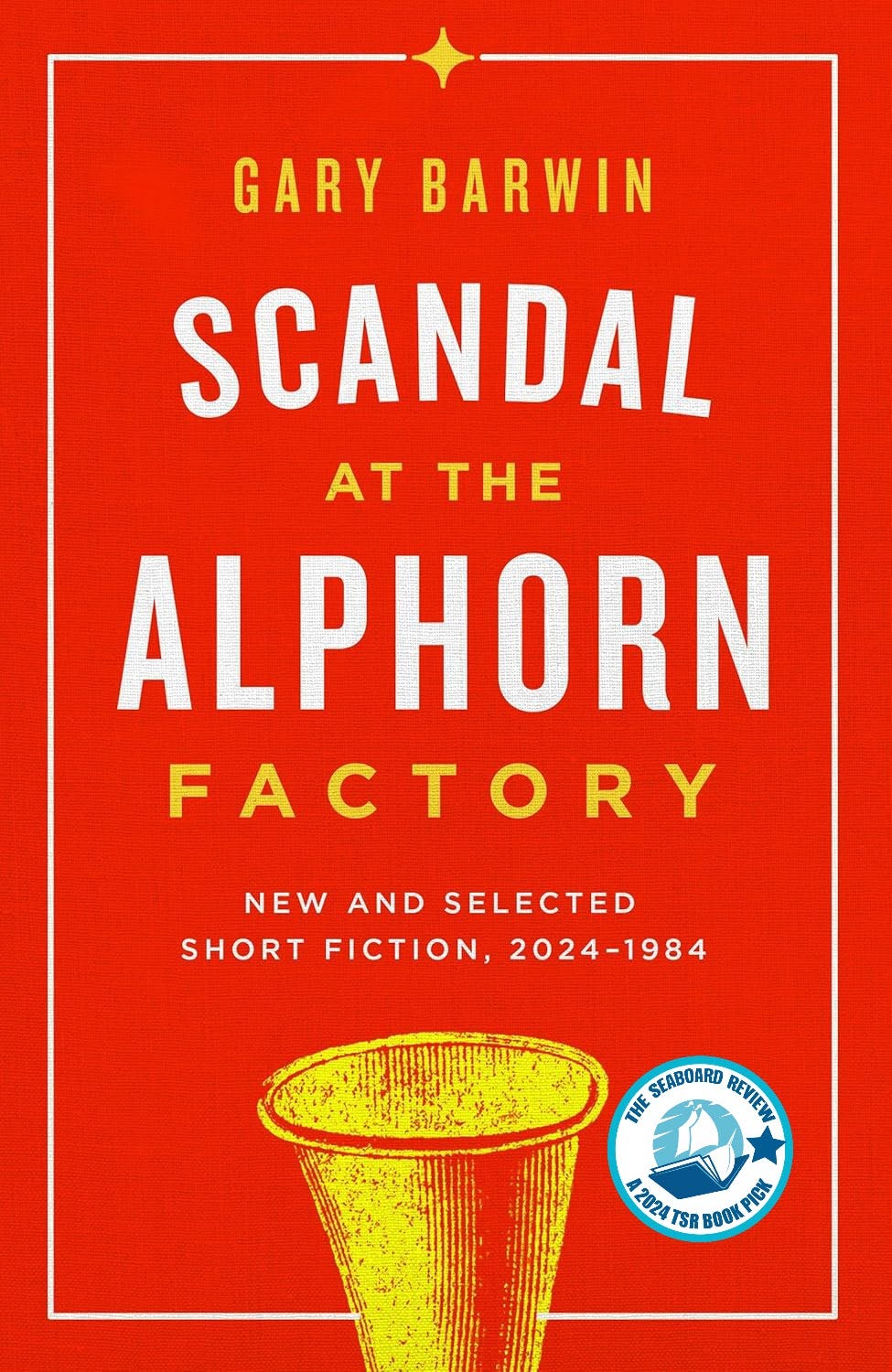

Yodeling in Yiddish: Scandal at the Alphorn Factory by Gary Barwin

A Short Fiction Review by Michael Greenstein

What is most noteworthy about Gary Barwin’s subtitle to Scandal at the Alphorn Factory is the order of dates – “New and Selected Short Fiction 2024-1984”. This reversal of the years’ progression points to Barwin’s techniques of reversal that result in irony, satire, and Jewish comedy, but also reveal his back to the future and forward to the past in his flash fiction, parables, fables, and allegories. If a Jewish calendar informs his writing, so too does a reversal in the Hebrew alphabet from right to left, which is featured in “Golemson,” the first story in this collection.

“Barwin is no ordinary reverser; he is also a centrifugal spinner of words and associations in multiple directions to surrealistic effect.”

Yet Barwin is no ordinary reverser; he is also a centrifugal spinner of words and associations in multiple directions to surrealistic effect. His “introduction of sorts” places “Lederhosen, Compassion, and Near-Death” into the centrifuge of his metaphysical wit and imagination – his zany brain that churns and charms at every turn. It all begins in a Northern Ireland school with an old man telling Irish fairy stories, and that Joycean gift of the gab seeps into these short fictions. “I feel the sound of this storyteller’s voice, the tropes of story, the space-time everywhere and nowhere of folktales.” These tropes and chronotopes range from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from domestic to cosmic, and intimate minuscules to the language of prolific creativity. Into Barwin’s centrifuge: “The made-up but already there. Words but not words. Like individual pieces of glass, they are also part of a larger pattern, each pattern part of an even larger mosaic.”

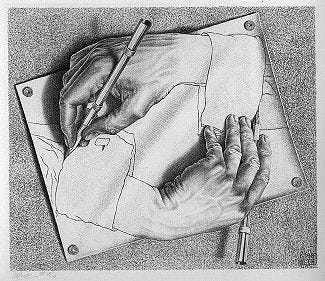

He invents and wanders through a wilderness of biblical myths, numbers, and letters: “What does it mean to be fictional for forty years?“ He and a friend imagine the headmaster’s daughter on the third floor of the school, and “we become some kind of coal-grimy Water Babies chimney sweep children fallen into the hearth beside her all-white four-poster while she in Victorian lace is a girl version of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang’s Truly Scrumptious.” These young wayfarers cross the boundaries of H. Rider Haggard to arrive at the Inimitable Dickens: “I have a small leather-bound book and point to an engraving of a bearded man on the front of the book – our leader, Charles Dickens, who stood for my identification with the perception of mystery, what language was, what story could be.” Dickens, Joyce, and Kafka scratch and stain his desk. “And, of course, this was itself a story. A story always tells the story of itself. The self-defining fiction of its own fiction. The two Escher hands drawing each other.” Always ambidextrous, Barwin mirrors the self-reflexive, surreal metafiction spun from his Borgesian library and labyrinth, parts of bodies drawn to each other but exploding in fissile fiction.

In this collection, Escher’s hands multiply and conduct polyphonic jazz rhythms against surreal strokes. The title of Barwin’s first published story, “Cosmic Herbert and the Pencil Forest,” already serves notice of his cosmic comedy and jousting jokes where his father’s medical resident misreads “Penis Forest,” which leads to the phallic fallacy, “the penis mightier than the sword.” Freudian slips penetrate the sylvan pastoral and public school, rendered as pubic school. Barwin dissects the alphabet to arrive at all the nuances of free association. He composes a villanelle about “my wonderful tuba made of bread,” the leavened music with its aftertaste of haste as he shares his body of selected stories. He explains his title: “I’m attracted to images that, like the alphorn, are both simple real-world objects and yet also uncanny and magical.” Alphorn, ram’s horn (shofar), and saxophone sound uncanny notes between Swiss Alps and Sinai, and between John Coltrane and temples across the Diaspora.

Magic and realism blend in his surreal musical centrifuge: “Alphorns are very basic wooden horns, but at the same time, they’re twelve feet long and used to signal from Swiss mountaintops.” Like the more compact shofar, “the alphorn reveals the wonder and strangeness of the world and the human imagination. Their doleful high-altitude bleating speaks to tenderness and uncertainty, and to the bewildering and marvellous situation of being alive.” For all its surreal zaniness, Barwin’s fiction contains elements of tenderness and uncertainty. His own commentary on the title is itself a story, as he explicates the connection between scandal and factory, keeping in mind that scandal derives from trap and stumbling block, impediments along the narrative roadway. Lederhosen, compassion, and near-death enter the cauldron of his imagination: “I’m moved by the juxtaposition of natural spaces (alpine meadows) and urban spaces (factories), of the poetic and the absurd.” This nutshell contains his aesthetic of compressed fiction that radiates and resonates.

Designs and patterns of gyroscopic improvisation: “One story leads to another, another iteration of story, just as each year I am a different iteration of myself, a different iteration of the possible me.” The nutshell bursts: “Same hat, different rabbit. // Same rabbi, different hat.” Escher’s sleight of hand displaces the rabbinic cap; strange loops braid the paradox of language, space-time, and story – “bewildering, strange, beautiful, painful, absurd, inspiring, breathtaking, surprising, funny.” Breathless after hyperventilating through the horn.

After this creative introduction that sorts things out and takes stock of lederhosen and compassion, we come face to face with the first story, “Golemson,” which finds the narrator waiting on a bench near a music store in Toronto. Although bench is an ordinary resting place, its Yiddish homonym “bentsh” sets in motion another dimension, for “bentsh” means to bless. And a particular blessing, to bentsh gomel, applies to a person who has escaped a near-death experience. Furthermore, gomel is an anagram of golem, the subject of this story. The narrator’s bench is surrounded by an atmosphere of night and fog that belongs to Dickens, Kafka, and Beckett. In addition, the music of Que Sera, Sera – the fate of what will be, will be – applies not only to the narrator on his bench of prayer, but to his narrative as well.

Prose rhythms match footsteps of anticipation as the narrator awaits his golem, just as the music students with their “ill-prepared fingers” in the nearby music store prepare for the making of the golem from clay. The narrator watches his golem approach: “Wearing a dark suit under a bowler hat, like Magritte or the man in his painting. Like me.” A surrealistic doppelganger, this twinning relationship is undercut by the jokester narrator’s “Kidding” comment. Place the lump of clay in a centrifuge and it becomes a “dreidel” or spinning top with Hebrew letters affixed. “If you do not know the Hebrew, you write something else. You freewrite. You edit.” This free-writing of creation and procreation is embedded in the narrator’s domestic life when husband and wife try to conceive: “Blood cells turning in a slow sarabande …. a viable zygote that would divide and divide and divide into our child.” From gyroscope to centrifuge: for every injunction to be fruitful and multiply, an equivalent force of division.

With Freudian slips of syringe and John Millington Synge, Barwin outwits folktale’s spin: “a golem can create the writing that created him. A kind of pearl writing the clam into being.” The story ends on the same bench with its own kabbalistic blessing.

Two poems bookend Scandal with their sounds. “The alphorn factory is vast beyond belief.” Vastness from the shortness of these little tales whose surreal mysteries suspend disbelief: “Rudi puts his lips to the mysterious / by the time it arrives at the other side / there is no other side.” Barwin’s breathless rides through imagination traverse scandals and factories, questioning notions of otherness and sidelines. His alphorn is the perfect vehicle (and tenor) for departures and arrivals of sound, sense, and no nonsense: “he isn’t able to stop building the alphorn.” Its endless echoes continue “across snowfields and meadows / through villages and between goats / it finally reaches the ocean’s lowest zone.” This spreading pastoral roams between summits and submarine depths. Indeed, the two bookended poems of 14 lines form a split sonnet: “to play the horn is to send / lungfulls of alpine air to deep-sea fish.” It is a song without end at the finale: “he builds and builds and the alphorn is everything / the long song that is home.” Barwin’s horn of plenty is all-encompassing, nourishing the near and far.

Also bookending Scandal is the image of the Möbius strip, the strange loop in Escher’s drawing hands and the double helix in DNA handed down through the generations. With its life of pi, “Radial” provides the first instance of a Möbius strip. “His mathematician father was dying, the father who would say that the body was an elaborate tube beginning with eating and breathing, ending with exhalation and excretion.” An alphorn is also an elaborate tube with its own anatomy of sounds. “A tube surrounded by the decorative hoo-ha of heart and lungs.” Father-son relationships abound in Barwin’s family romance and Oedipal complexities. “The small father, the tall son, each with digits of ñ tattooed on their body.” The next sentence turns radial, an anatomy lesson with Gödel’s mathematics, the prose and tropes in a gyroscope: “Round and round, the looping digits, the initial number 3 over the heart, then decimal points and numbers running across the chest, the nipple, the ribs, back to the shoulder bone, spine, shoulder bone, then the ribs, then around front again, spiralling down and down and down, and then like a Gordian snake twisting up, over and under, intertwining with itself, a Möbius strip, a cat’s cradle …. the never-ending, the not-repeating.” No mere bracelet about the bone, this double helix belongs to a genetic code that links generations back to a grandfather’s arm tattooed with numbers from a concentration camp. Metaphysical and metafictional, “Radial” exhibits relics – “Patterns like small waves rising in a numerical ocean without shores,” and the sound waves of an alphorn and golem.

The image recurs in “Like Bozo’s Nose of Time Itself,” a title that proceeds through simile, alphorn assonance, anatomy, clowning, and abstract timing. The story begins between the rush of hyperventilation and a pause of contemplation, and between domestic and cosmic scope: “All those years dashing off to work, leaving my sheets a knotted mess of snores, and now here I am, standing before a sheet of clouds that it’s my job to fold over a bed big as sky.” The next sentence probes abstract and immediate space: “I wondered, back on earth, if space would disappoint me, but subject and object have disappeared, lifted away like the box top separating cereal from milk-filled bowl.” From box top to big top, Bozo’s carnivalesque sensibility sniffs meanings in a tent and carousel of self-reflexive mirrors: “I am like a Möbius strip, my inside and out all one surface.” His kaleidoscopic wallpaper mixes the mundane and the metaphysical: “On a lime-green riverbank, Descartes was making sandwiches. Schopenhauer and Immanuel Kant were fishing from a boat.”

The boatman searches his soul and surroundings: “And I would like a boat, plummeting a million kilometres up toward myself, wrapping a lime around my eternal soul and pulling hard, tacking around my illuminated veins that spiral around me like distant galaxies.” Bozo’s serious jokes abound in similes, “like a punchline that goes on forever” in the pathos of a factory with its million windows of fiction. Barwin’s surrealism combines Chagallian levitation with Wallace Stevens’s supreme fiction, as he puzzles puzzles. Clockwise, counter-clockwise, and otherwise, Barwin’s page turns itself and turns itself, orchestrating each instrument through comedy and lyrical longing.

About the Author

Gary Barwin is a writer, composer, and multidisciplinary artist. He is the author of 31 books including Imagining Imagining: Essays on Language, Identity and Infinity and Nothing the Same, Everything Haunted: The Ballad of Motl the Cowboy which won the Canadian Jewish Literary Award, was shortlisted for the Vine Award, and was chosen for Hamilton Reads 2023. His national bestselling novel Yiddish for Pirates won the Leacock Medal for Humour and the Canadian Jewish Literary Award, was a finalist for the Governor General's Award for Fiction and the Scotiabank Giller Prize and was long-listed for Canada Reads. His 2022 poetry collection, The Most Charming Creatures won the Canadian Jewish Literary Award. With a PhD in music composition, he has been a writer-in-residence and has taught at many universities, colleges, and libraries. He lives in Hamilton and at garybarwin.com

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Assembly Press (Sept. 3 2024)

Language : English

Paperback : 304 pages

ISBN-10 : 1738009882

ISBN-13 : 978-1738009886